Image credit: Pexels

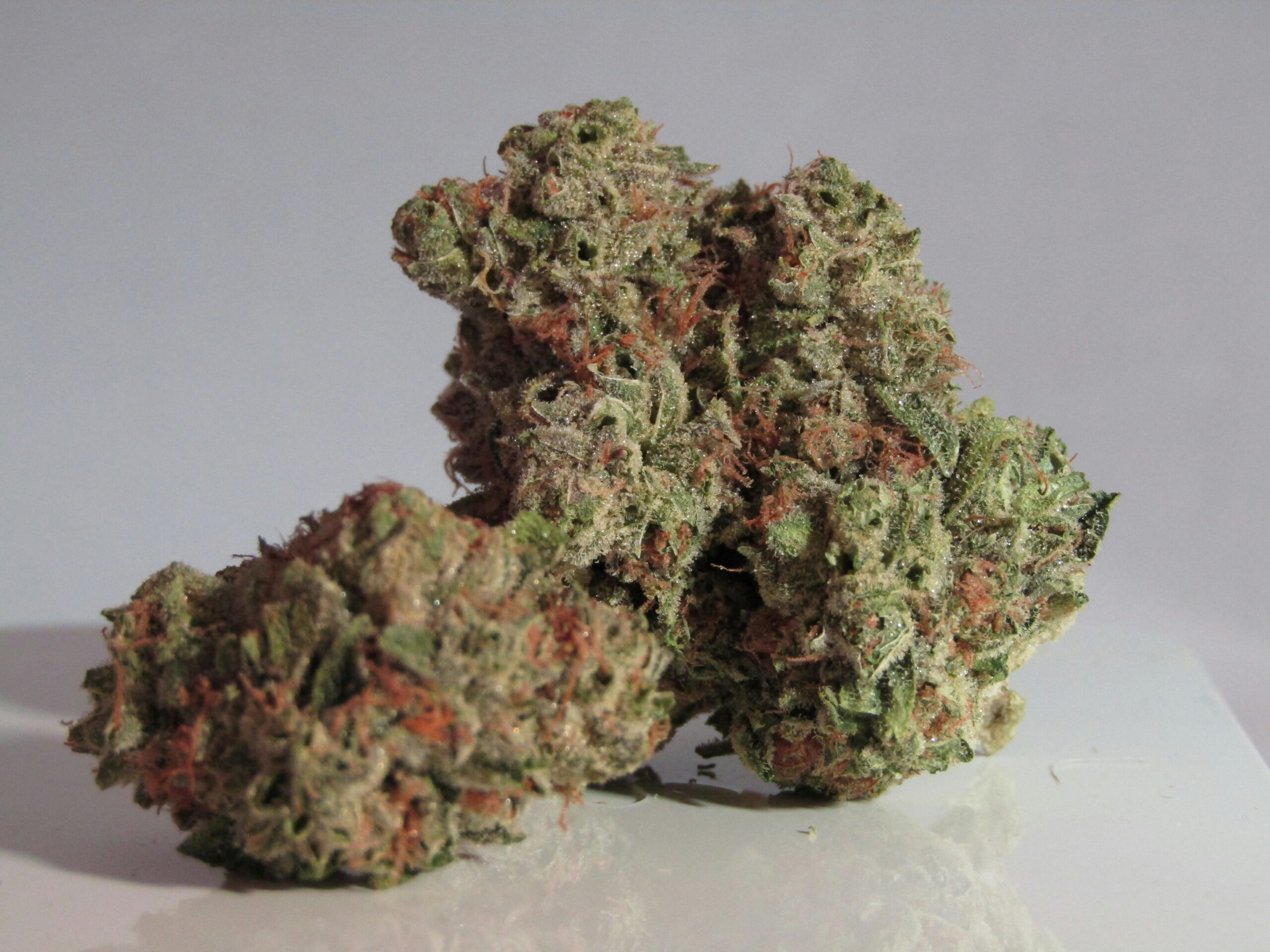

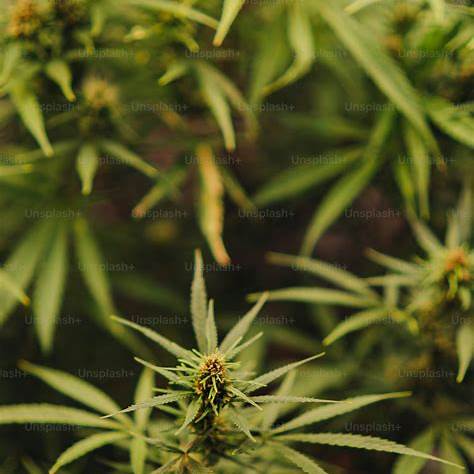

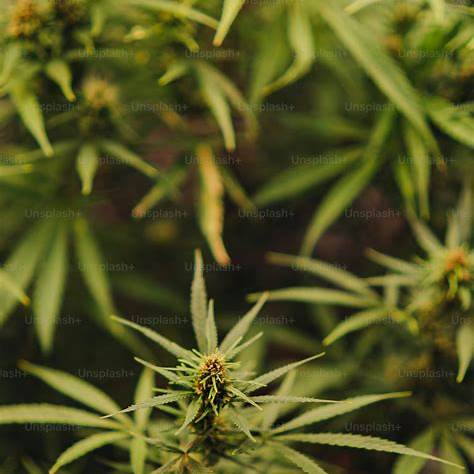

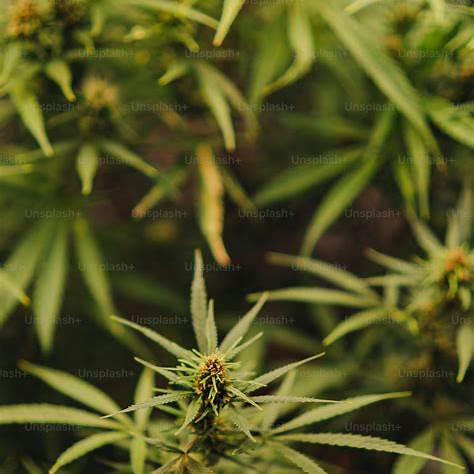

In December of 2018, St. Vincent and the Grenadines provided amnesty to traditional cannabis farmers, ensuring that Rastafarian growers could start a medical cannabis industry. The amnesty process also involved the limited decriminalization of the drug’s use and the establishment of a medical cannabis industry with associated regulatory bodies.

Before 2018’s Amnesty Decision

Before the historic change took effect, Rastafarian cannabis farmers like Bobbis Matthews had to hide illegal cannabis fields in the mountains—while living in constant fear of United States-backed anti-narcotics operations. As Matthews told The Guardian, U.S. helicopters would destroy millions of dollars worth of cannabis at least three times a year.

“In those days,” Matthews recalled, “it felt like you couldn’t even say the word marijuana because just to say marijuana, you could get arrested.”

“We had a song called Helicopter,” said conservationist and Rastafarian cannabis farmer Erasto Robertson. “It was about the panic and franticness whenever you hear the sound of a helicopter. Back then, we had to develop a good relationship with the police; and some would protect us because the policeman sometimes was the brother of the marijuana farmer. They were the same blood, so they were protecting their family and the wealth of their family.”

Putting Community First

The 2018 change came as a result of consultations with the local Rastafarian community and St. Vincent and the Grenadines’ traditional farmers. For the farmers, marijuana is certainly a means of income, but many of them have a similar view as the Rastafarians. Rastafarians believe that the plant’s properties can promote religious experiences through spiritual connection and meditation, but also that the plant has general medical benefits.

Rastafarians and the Medical Uses of Marijuana

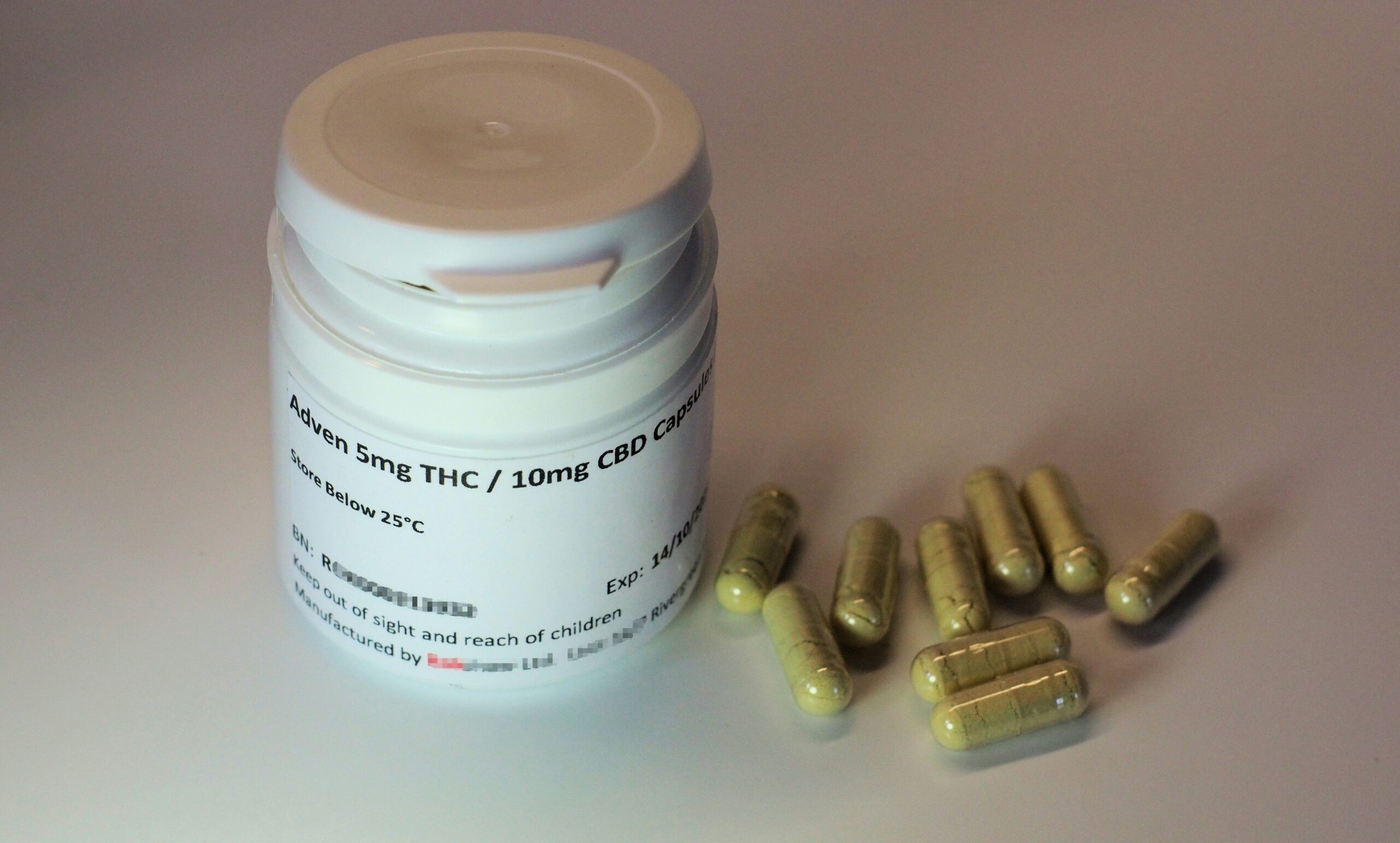

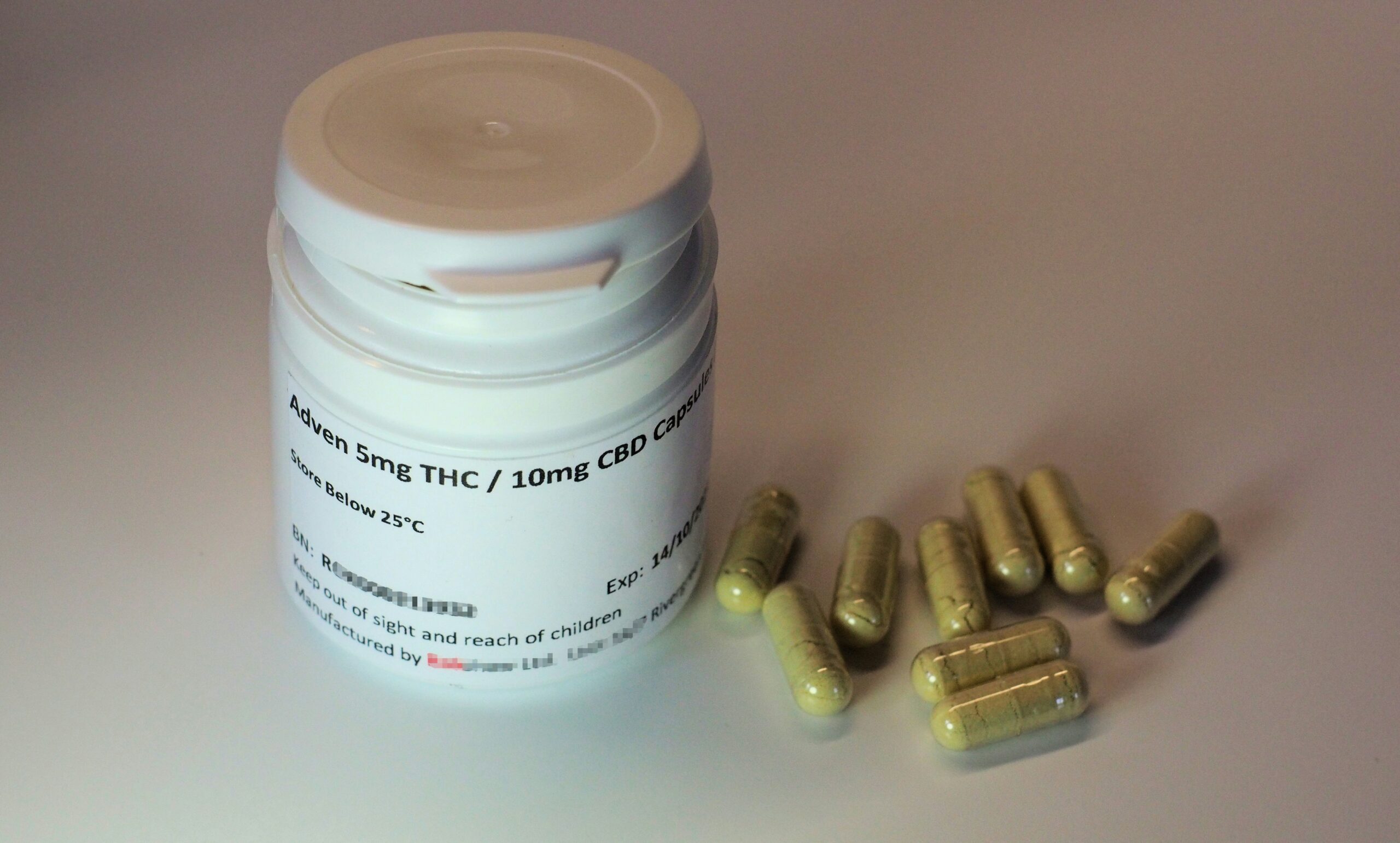

While Western science has just begun to uncover the medical benefits of marijuana, Rastafarian communities have long recognized the plant’s ability to treat pain, asthma, and epilepsy, among other medical issues. Now, St. Vincent and the Grenadines supports the traditional medical marijuana industry. Alongside the amnesty decision, farmers can apply for a license to grow marijuana, and companies that produce marijuana products must buy 10% of their plants from traditional farmers.

It is a welcome decision for Rastafarians and traditional farmers alike, but the challenge for St. Vincent and the Grenadines and other Caribbean countries remains centered on wealth disparity and stigma. Though the legal cannabis industry is expected to reach $58 billion in sales by 2028, opportunities for international trade are limited. Caribbean nations must compete with wealthy nations like Canada while being more vulnerable to natural disasters.

The Risk of Growing in St. Vincent and the Grenadines

In 2021, a volcanic eruption destroyed nearly all produce in St. Vincent and the Grenadines, including fields of cannabis. As Matthews remembered it, there were “Six, eight inches of ash. This entire landscape was covered with that amount of ash. I lost my entire field. But not just me; every ganja farmer—every farmer for that matter, every tomato farmer, every sweet potato farmer.”

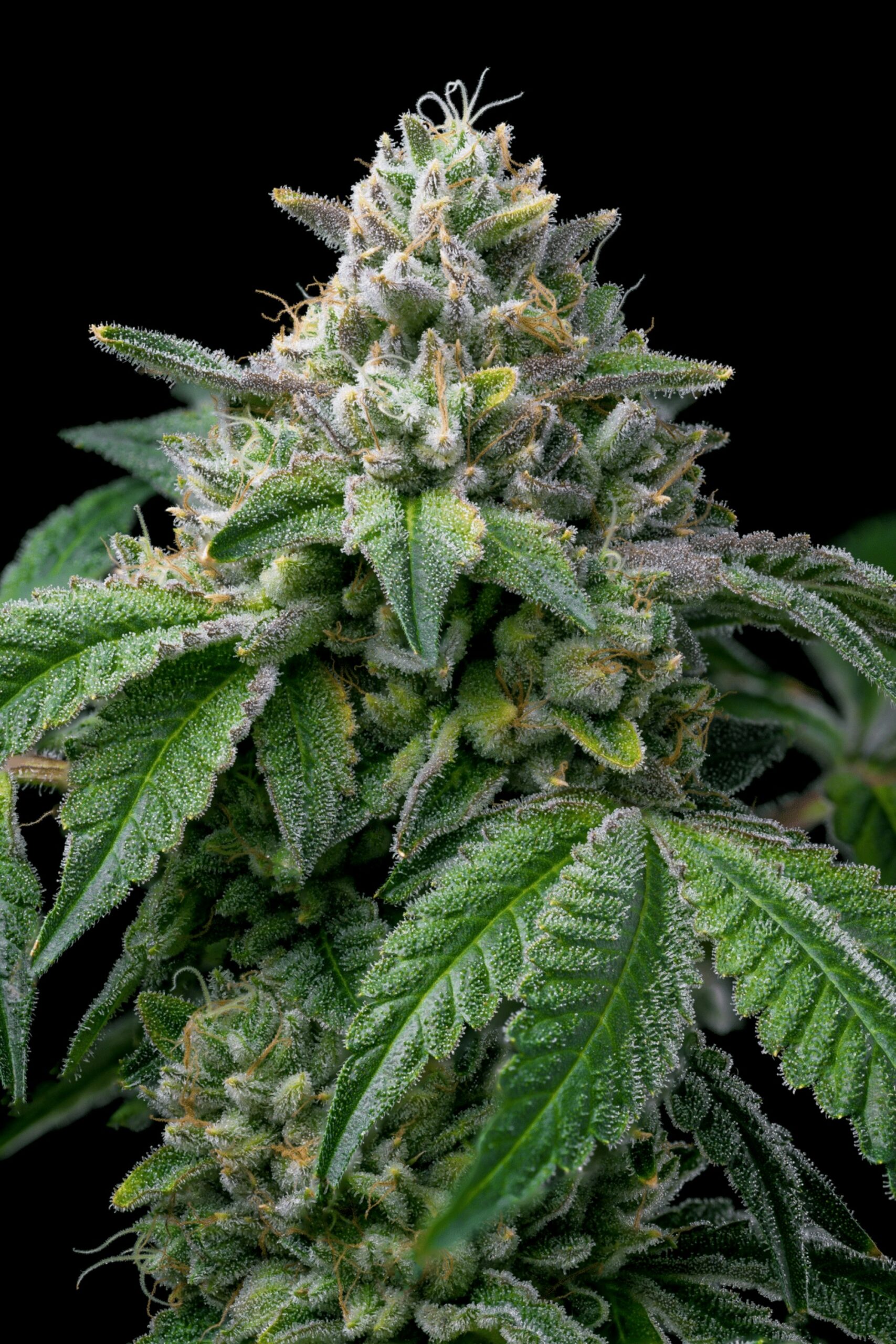

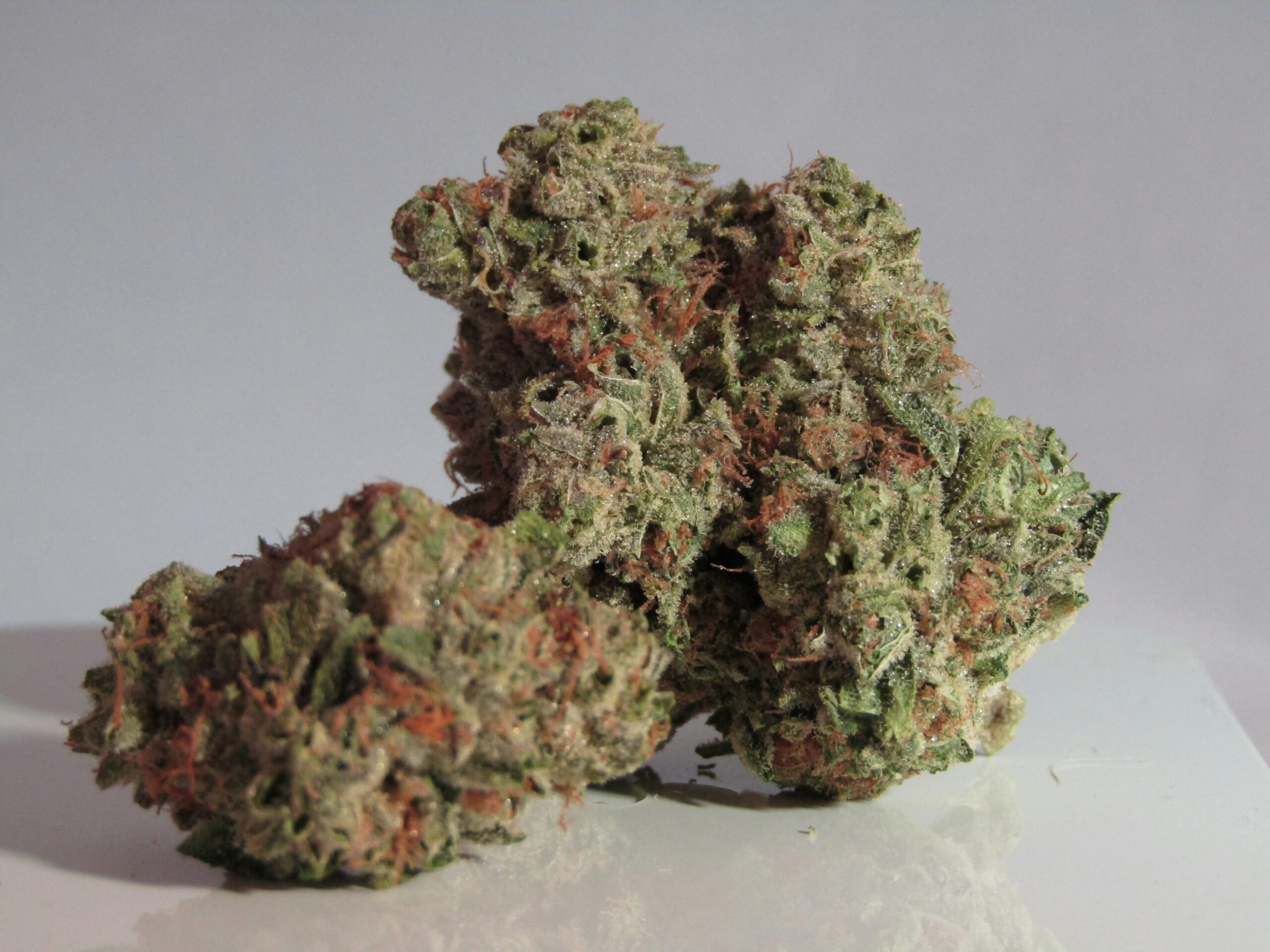

St. Vincent and the Grenadines’ rare andosol volcanic soil might carry the risk of destructive eruptions, but at the same time, it is ideal for producing a uniquely high-quality cannabis harvest. It is possible that the island nation will become known for the distinct quality of its cannabis rather than its production volume, encouraging tourism and better prices for farmers.

A Reflection of Caribbean Change

St. Vincent and the Grenadines is one of many Caribbean countries that have decriminalized or plan to decriminalize cannabis for recreational, medical, or spiritual use.

“The Caribbean is poised to become the first intensive zone of medicinal cannabis legalisation in the world,” said Dr. Jerrol Thompson, CEO of the St. Vincent and the Grenadines Cannabis Authority. “Jamaica was the first in 2015, followed by Saint Vincent and the Grenadines in 2018. Since then, more islands have followed, including Antigua, Barbados, and Saint Kitts and Nevis.”