Image credit: Unsplash

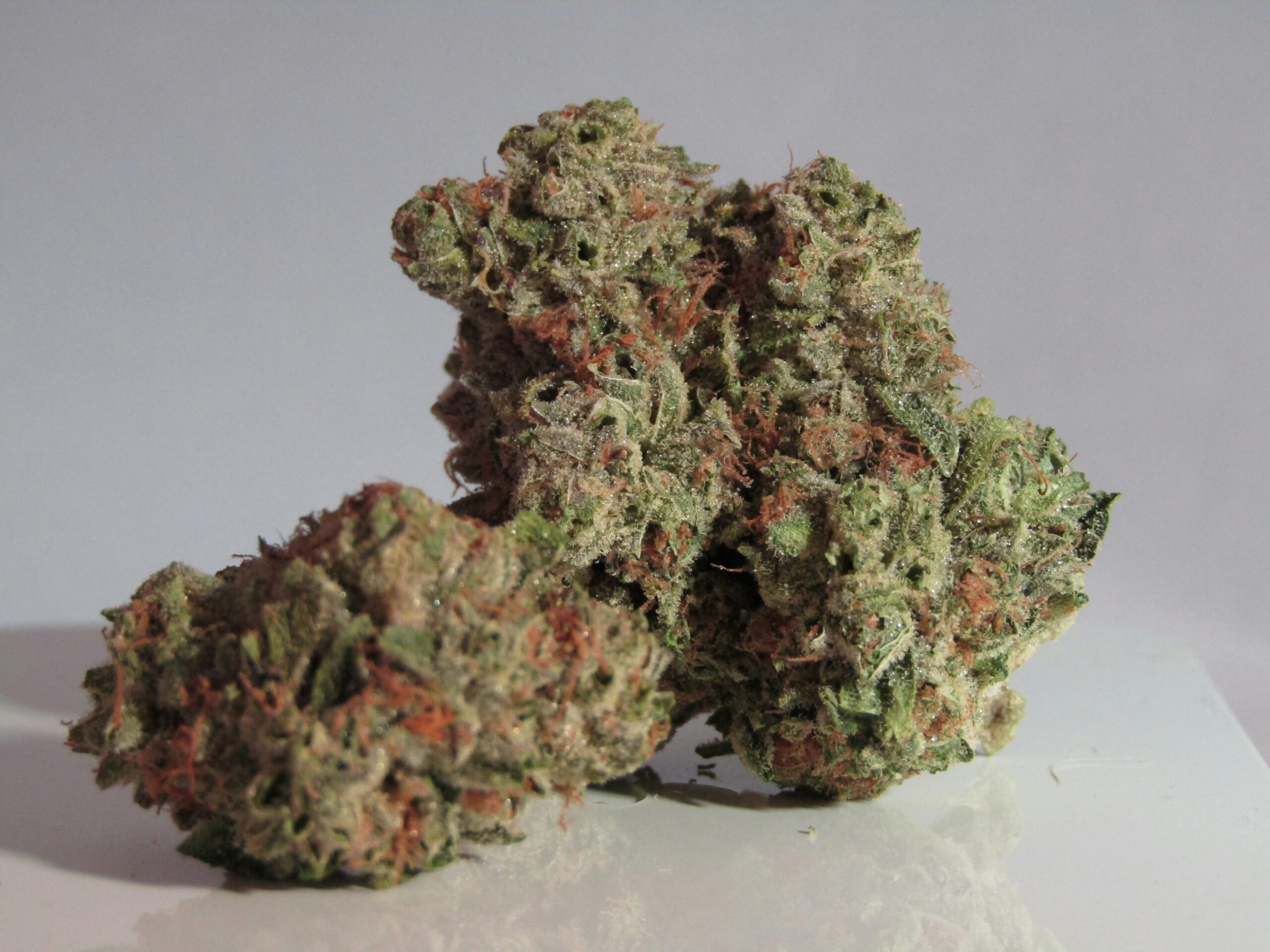

A new study has thrown a spotlight on the alarming connection between cannabis use during those tumultuous teenage years and the development of psychotic disorders down the road. This research reveals that the age factor plays a crucial role, making teenagers particularly prone to the impact of cannabis on their still-evolving brains. The eye-popping results, published in the journal Psychological Medicine, show that teens indulging in cannabis face an 11 times higher risk of developing psychotic disorders compared to their cannabis-free counterparts.

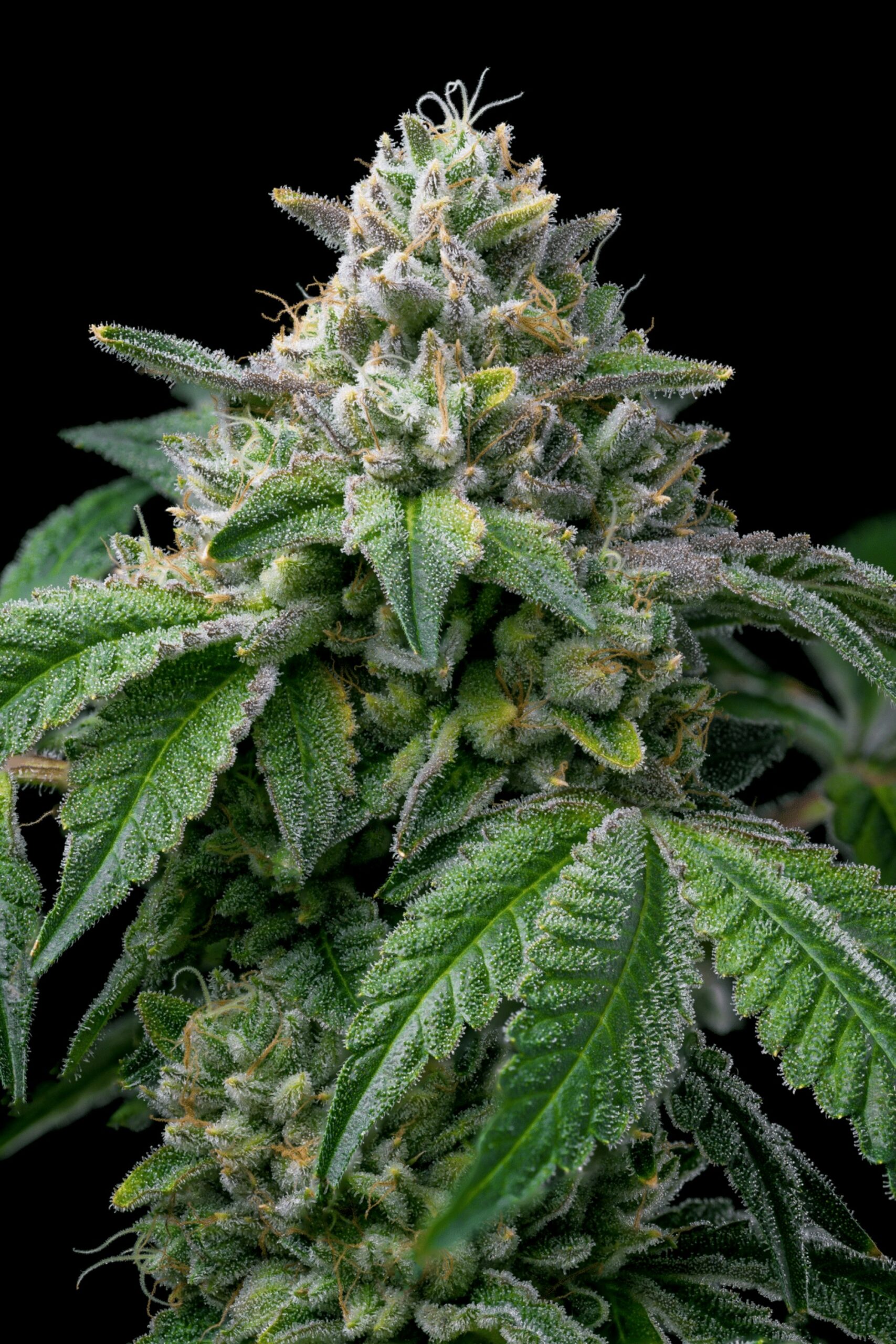

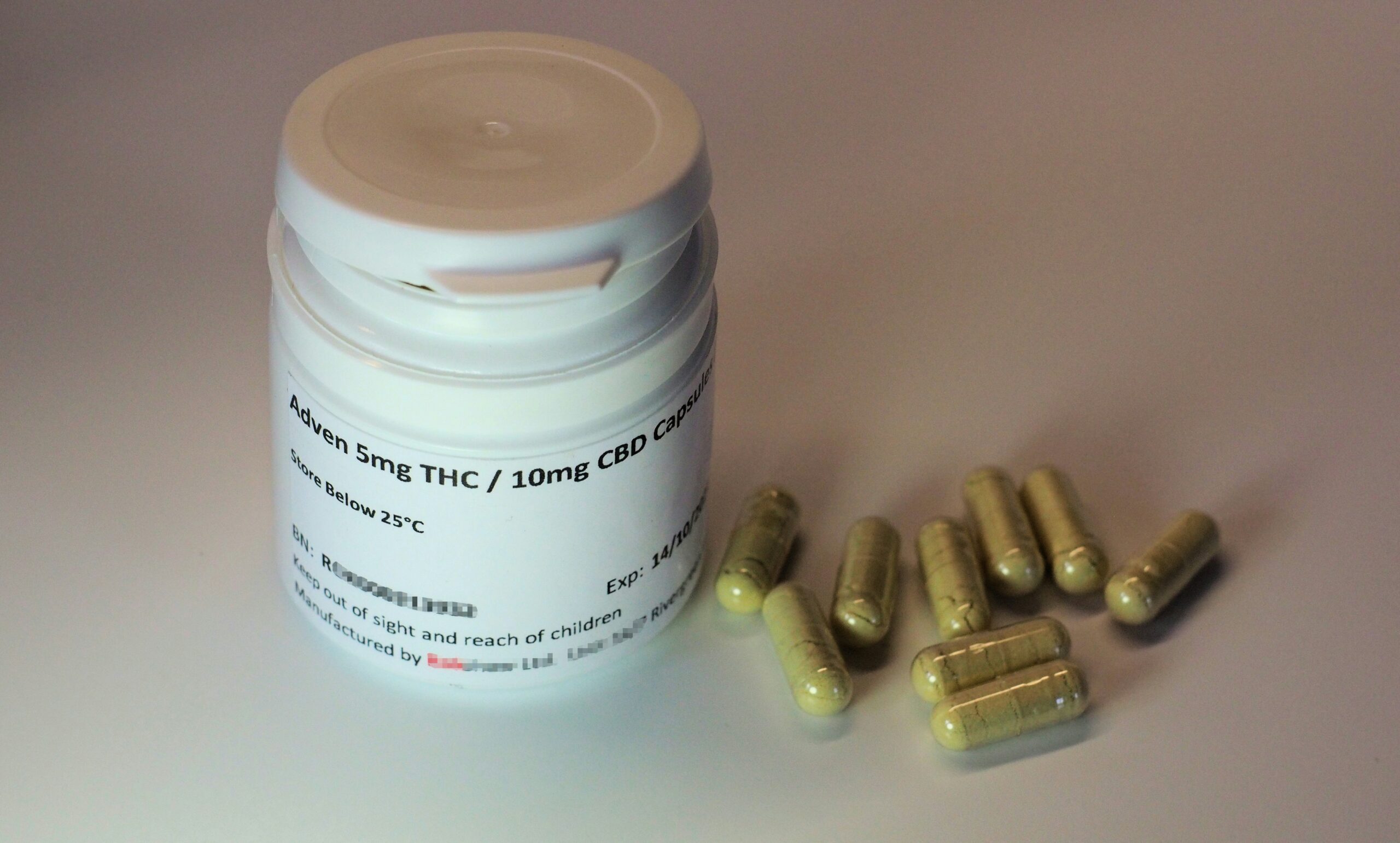

This revelation throws a wrench into older studies, which might not hold water anymore, considering the THC levels in Canadian cannabis have rocketed from a mere 1% to a whopping 20% over the last forty years. This sharp spike in THC content stirs up fresh worries about the mental health fallout for today’s youngsters, underlining the pressing need for up-to-date and precise data to grasp the risks linked with modern cannabis use.

In a trailblazing study, boffins from the University of Toronto, the Center for Addiction and Mental Health, and ICES have stitched together survey data from over 11,000 youths in Ontario, Canada, with their health service records. This pioneering research is the first to reveal an age-dependent connection between self-reported cannabis use and subsequent diagnoses of psychotic disorders. This eye-opening discovery adds another piece to the ever-growing jigsaw puzzle of understanding the mental health risks associated with cannabis use.

André McDonald, the lead author, who conducted the study at ICES as part of his PhD at the University of Toronto, stated: “We found a very strong association between cannabis use and risk of psychotic disorder in adolescence. Surprisingly, we didn’t find evidence of association in young adulthood.”

He added, “These findings are consistent with the neurodevelopmental theory that teens are especially vulnerable to the effects of cannabis.”

Of the teens who ended up hospitalized or visited an emergency department for a psychotic disorder, roughly 5 in 6 had reported previous cannabis use. McDonald stated that the majority of teens who use cannabis “will not develop a psychotic disorder.” McDonald notes, “According to these data, most teens who are diagnosed with a psychotic disorder” are likely to “have a history of cannabis use.”

The researchers could not rule out that teens may have been self-medicating with cannabis before receiving their clinical diagnosis. They could also not account for genetic factors or histories of trauma.

The limitations as a result of this lack of data make it impossible to say that cannabis use alone causes psychotic disorders in teens. The authors of the study note that their estimates are only approximate, and state that further studies with larger sample sizes are required.

Susan Brody, an affiliate scientist at ICES and an associate professor at the University of Toronto’s Dalla Lana School of Public Health, who was a senior author of the study, stated, “As commercialized cannabis products have become more widely available, and have a higher THC content, the development of prevention strategies targeting teens is more important than ever.”

It was noted during the study that Canadian youth aged 15 to 24 are among the heaviest users of cannabis in the world. The National Library of Medicine indicated that the adverse risks of cannabis use are concerning, but that there are gaps in their understanding of risks and harms to youth.